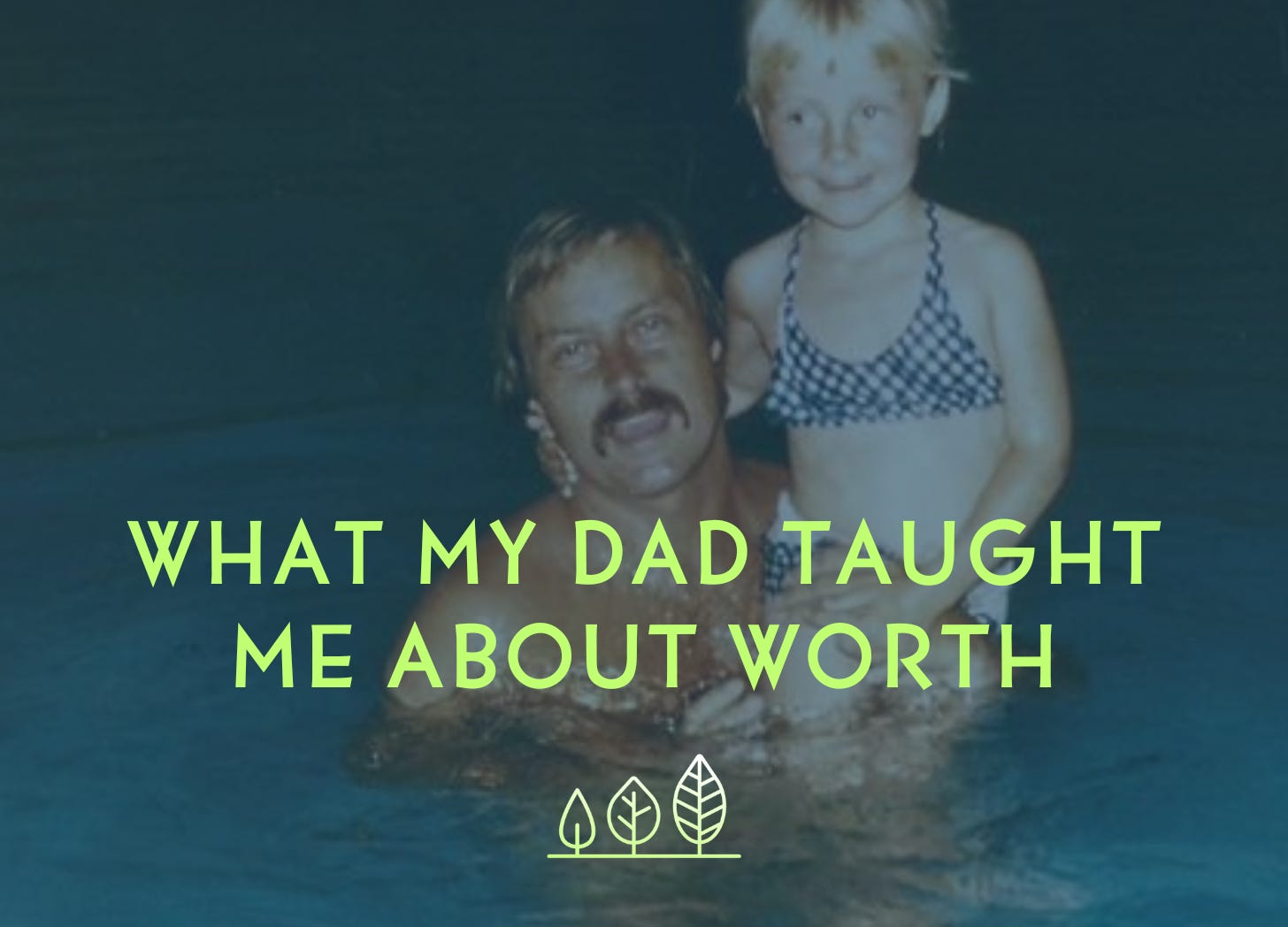

My dad just died. Here's what he taught me about worth.

Less morose than this headline suggests. And relevant regardless of whether you knew my dad or not.

My dad died last week.

A day before his 76th birthday, the long-term care home called to let me know that he’d been found on the floor, no longer breathing, likely from a heart attack.

I’m still processing…or perhaps I haven’t really started…or more likely, I processed and grieved this inevitable reality many moons ago.

He hadn’t been well for a long time. The past two years started with an emergency trip to the hospital, a month long stay, and the very real possibility that he wouldn’t get out.

Somehow he rallied and survived, but not with enough gusto to go back to independent living. He’d been in a long-term care home ever since.

And on Saturday, May 11th, the day before his birthday and Mother’s day, I got the call. It wasn’t unexpected, but it wasn’t expected either. He’d been stable for a while, and while there’d been many moments I’d thought the end was near, this wasn’t one of them.

We are all doing our best, and if I’m being honest, I’m glad that his suffering and poor quality of life is over.

The word bittersweet exists for a reason.

As I reflect on his life and connect with people from his past, I find myself considering what impact he had on me…how he shaped the person I’ve become.

I have his eyes; bulgy and big. I have his high forehead…a genetic gift passed on by my Icelandic grandmother. And I have his smile. The rest, as I’ve been told by anyone who knows my mom and me, is a reflection of her.

But what I think about most is how he shaped my views on work, (self)-worth, leadership, ambition and purpose — both in healthy, productive ways and also in unhealthy, sometimes even destructive ways.

Here’s what I’ve learned, in no particular order…

Put your values first

I don’t recall my dad ever using the word ‘values’ to describe his non-negotiables — certainly not in the way I speak about them now.

But he lived them, imperfectly.

And while he never named his, I know we shared two: curiosity and fairness.

My dad was an avid reader and learner. He loved to talk politics and prided himself on being in-the-know. When we cleaned out his apartment after moving him into the long-term care facility, I sorted through his books, which included everything from Seneca to Machiavelli to Joan Didion to Nelson Mandela.

From the moment I can remember, my dad was always advocating for the underdog, the oppressed, the vulnerable. He had zero tolerance for anyone who told a racist joke, who minimized someone’s suffering or who took advantage of someone else.

In his role as a city planner, he was often involved in contentious issues that faced city council.

He’d call it out — publicly if needed — and he made sure my brother and I knew what had happened wasn’t acceptable. He believed deeply in fairness and justice.

Did he create a few haters along the way? Absolutely.

Did he care? Absolutely not.

He put his values first, and believed that if he was living by them then the noise of other people’s opinions wasn’t important enough to pay attention to.

It’s likely he took that too far at times (see section below re: extremes), but more often than not, it made him a respected leader at the City as people knew he had their backs.

He taught me the importance of leadership. And he never once doubted in my ability to be a leader in my own right — first as a girl, then later as a woman.

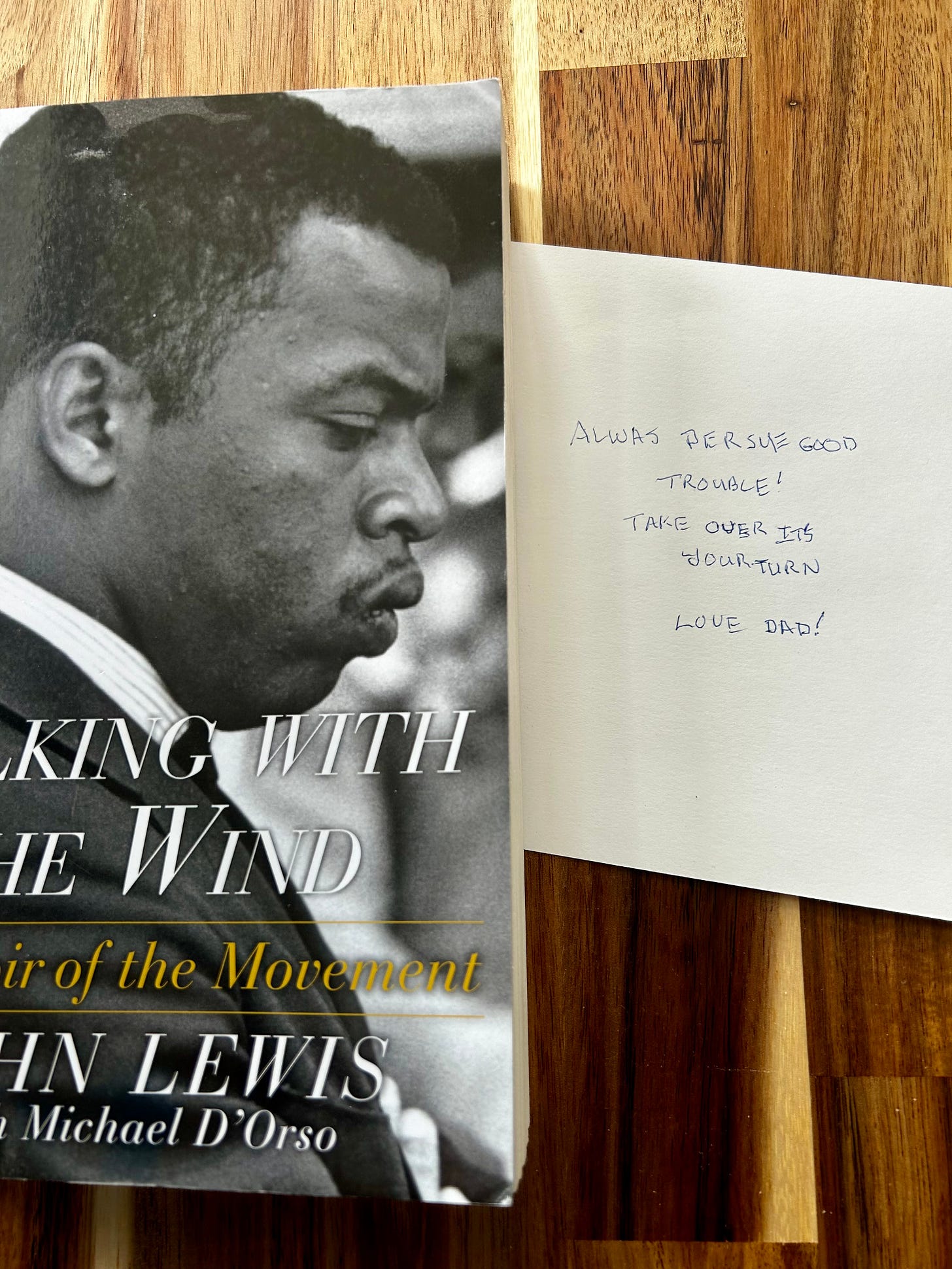

A couple of years ago, he gave me (and everyone else in our family) a copy of John Lewis’ memoir, Walking with the Wind. In my card he wrote…

Lessons learned:

➡️ Living and leading by our values shape our lives, and becomes what we’re remembered by. My dad was far from perfect and he pissed a lot of people off, but everyone I’ve ever met who knew him said that he was a man of integrity and of his word. Values are only words unless they’re lived every day. I’m proud of him for living his.

➡️ When we’re deeply connected to our values, we can hold our head up in hard times and ignore the haters (or even naysayers) who tell us we’re wrong. It doesn’t mean we shouldn’t receive feedback gracefully, but it does mean that we have a filter (values) to put it all through to decide what we’ll use and what we’ll discard.

➡️ Speaking up for what you believe matters. It’s not enough to know something is wrong and stay quiet. He recognized his power and privilege early and used it to advocate for those whose voices weren’t heard. If I got nothing else from him, I’m glad I got his sense of fairness and justice. I live it imperfectly, but I’m trying.

Purpose keeps us going and without it, we flounder

From the moment he finished university until retirement, my dad worked as a city planner here in Calgary. He had a reputation of working hard, caring deeply, questioning regularly and never settling for the status quo.

Work was everything to him: he wasn’t a workaholic, but it was the centre of his focus and what he thought about and talked about much of the time.

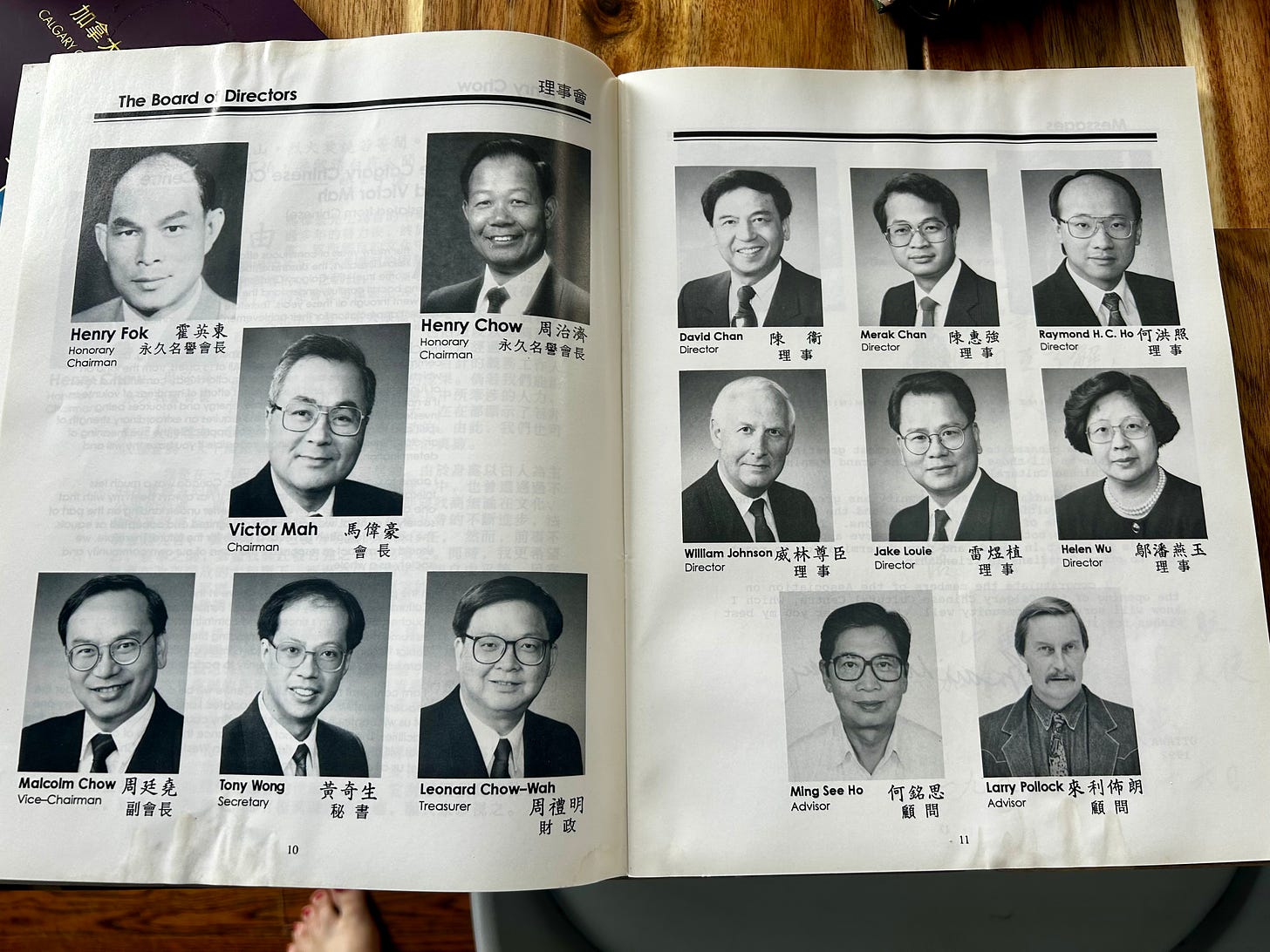

His greatest point of pride was his role in the Chinese Cultural Centre development. Last summer, my brother and I took him there to tour around. We found his name in media clips in their museum, and his dementia quieted a bit as he shared memories and people from the past. As we left, the staff found a tribute magazine from the 90’s with his picture in it, and gave it to him to keep. When I packed up his stuff the day after his death, this was sitting on top of his pile of papers.

He put everything into his projects: they weren’t just tasks on his to-do list, they were meaningful contributions to the city he cared deeply about.

When he retired early, due to reasons I won’t share here, it wasn’t long before he started to flounder. He lost connection to his central purpose, and while he still had other things in his life (family, golf, reading, politics), they weren’t enough.

Without a focus to orient his life around, he started to fade…slowly at first, then quickly. His isolation grew and his alcohol addiction took centre stage. He was never able to find a cause…a quest…a purpose that helped him find meaning and connection after work.

This is always a reminder to me, as someone who loves work as much as he did, and who doesn’t come by hobbies and fun-for-the-sake-of-it easily, that life is much bigger than work.

Lessons learned:

➡️ When our purpose is tied to only one thing (namely work), it’s a far fall if that goes away suddenly. Having a more well-rounded sense of purpose and meaning buffers us from external (or internal) changes we don’t see coming.

➡️ Having a sense of purpose is a powerful motivator and action-instigator. When we can tie our leadership to something that matters to us, we’ll go to many lengths to make it happen. When we’re disconnected from our bigger why, burnout or apathy isn’t far away — going through the motions isn’t a sustainable way to live.

Learning to rest isn’t easy, but it’s necessary

I’ve already written about my relationship with the word ‘lazy’ and how my dad inadvertently shaped it. You can read the full story here.

But I can’t write a post about how my dad informed my relationship with worth without acknowledging his skewed view of what it meant to rest.

Growing up, I can’t remember a time my dad relaxed — truly relaxed.

The only memories I have of him having fun and appearing relaxed is when we’d have people over for dinner and he’d be a few beer in. Lionel Richie or James Taylor or Paul Simon’s Graceland would be playing and I’d for a moment, get to see my dad smile and settle into himself (noting that it always took alcohol to get there).

As a kid we’d go camping, and while my mom would be playing her guitar around the campfire, my dad would sit for a few moments and then get up to ‘do something’ — chop wood, go for a jog around the campsite, fix the tent trailer or anything that would keep him busy. On the day we were set to leave, he’d be up at the crack of dawn, cleaning up and getting us out of there as fast as possible.

(if anyone wants to know where my ridiculous desire to be uber-early to everything comes from, all signs point to this)

To be idle was to be lazy. And lazy was not a good thing.

Looking back, I can see that it was all likely one massive attempt to avoid all the stuff he’d been avoiding for years. Keep busy, keep moving, don’t feel, don’t fight it.

Don’t stop going.

Lessons Learned:

➡️ A relentless desire to keep moving and never pausing to reflect, rest or recover isn’t a sign of high-performance, it’s a sign of avoidance and self-destruction (hard truth, I know). The top performers in all fields who stay at the top over the long haul, recognize the critical need to incorporate rest into their lives without judgement.

➡️ It doesn’t have to be hard to count. Gosh, if I could go back and say anything to my dad at various points in his life, it would have been that. To let some things be easy, to cut himself way more slack and to enjoy the process once in a while.

Shame will always trump our worth

Shit went down in my dad’s life that I’ll likely never know about.

I know that his dad died when he was just 13 (and his dad was 70). I know that he used to say he had zero memories of his father, who as a mother of a 13-year-old, feels incomprehensible to me.

I know that his mother and sister and he were alcoholics. I know that nobody talked about anything. I know that it was a way to cope…I just don’t know from what.

And I know that my dad battled those unspoken, perhaps unacknowledged, demons for the rest of his life…even when my mom, my almost-step-mom-to-be, my brother and I all begged him to get help. He tried, but it never took.

Because shame is a powerful force.

And left unaddressed or not shared with others, it festers and rots and clouds our ability to see a healthy path forward.

It robs us of our worth, and tells us we’re less than enough and that we’ve never been enough.

I often wonder what might be different if my dad had ever been willing to share parts of his early years with someone…anyone. I wonder what secrets died with him last Saturday, and how it influenced everything — including me.

But what I don’t wonder about is how destructive it was to his sense of self. Early on, I always had the feeling that he was chasing something…or perhaps running from something.

I wish I could have helped him, but I also know that he wasn’t willing to open doors he long ago shut.

Lessons Learned:

➡️ Nobody goes through this life without incredibly hard things happening (recognizing that this is more true for some than others for a myriad of reasons). But when we keep it hidden from others…and from ourselves…we hold it all inside us in ways that can only fester and rot over time. Find safe people to share your stuff with. Get help early. Never assume you’re alone.

➡️ Shame clouds our sense of self. It makes us believe things about ourselves that aren’t true. It keeps us closed off from true connection. And it tells us that we’ll never be enough because of the mistakes we’ve made or because of what’s happened to us. Shame offers us a distorted view of the truth and keeps us from living as our truest selves. At every turn, we have to find ways to work through our shame and self-blame so that we can see what’s actually true — that we are inherently worthy, simply because we exist.

Balance is BS, but extremes aren’t great either

My dad lived a life of extremes. Half-assing anything was not an option.

His drive had him push himself in ways that were both incredibly effective and terribly destructive.

This showed up in all areas of his life, but nowhere was it more pronounced that in his approach to exercise.

Throughout my childhood and teen years, I can’t remember a week where my dad wasn’t doing something active. He rode his bike to City Hall every morning — even in the dead of winter — and he’d run up and down the hill in Edworthy Park over and over again each weekend. He’d sign up for races, spend the day at the golf course and go for long-weekend fishing trips with friends. When he’d take me with the Olympic Oval to skate, we didn’t just skate in circles, we’d sprint as fast as we could until the point of exhaustion.

Most of this was healthy exercise that kept him in far better physical condition (minus the drinking and smoking) than his peers.

But as I got older, I started to notice that while a quiet, beer-filled fishing trip might be relaxing for him, his relentless quest to push himself harder and harder was taking a toll (not to mention the toll it took on my mom).

Once he retired, he not only felt the effects of his dwindling sense of purpose but with it, the effects of being so hard on his physical body. Over the next 20 years, he struggled with many physical ailments from a torn achilles, to aching knees, to nerve damage in his hands. By the time he died at 75, he moved more like a 95-year-old. To those who loved him, this was such a devastating turn given his life-long desire to stay in shape and prove his worth through physical endeavours.

Lessons Learned:

➡️ Our ambition and drive to succeed can be a powerful push, but it’s got to be sustainable over time or the cracks will eventually show. We can only sustain a high performing pace for so long if we don’t also bake in other strategies like rest and recovery into the mix. Eventually, we run out of gas and have to refill. And if we run on empty for too long, the engine and parts start to wear down to a point of no return.

➡️ When we live in extremes we miss the joy in the process and the growth along the way. I wish my dad had taken a moment here and there to reflect on all he’d accomplished instead of constantly trying to one-up himself. He missed so many moments of celebration because he was hyper-fixated on his next quest. I get that from him, and it’s a conscious, daily decision to take a beat and acknowledge my small wins along the way.

One of my guiding principles in life is to live and lead in the both/and instead of the either/or. I actively work to find nuance and the grey in most situations.

Looking back on how my dad’s life shaped my sense of worth, I find a lot of grey.

⭐ He was both an incredibly hard worker AND a person just trying to cope with the hard parts of life.

⭐ He was kind, concerned and committed to everyone he cared about AND he struggled to offer that to himself.

⭐ He lived by his values AND sometimes he held them so tightly he left little room for give.

⭐ He had a complicated life AND he did the very best he could with what he had.

My dad was a good man, who led a tough (internal) life.

He was well-loved, well-respected and well-intentioned. I’m glad he’s no longer suffering, but I will miss him deeply.

His passing is a reminder to me to live my life more fully and to stop playing small for fear of what others may think of me. And to enjoy the process more rather than feeling like I’m always 10 steps behind where I should be.

So Dad? I promise to get into some good trouble. It is my turn.

And it’s your turn to rest. ❤️

Thanks Pepper. ☺️ And I agree - I think it’s in the challenges that we learn the most. I take the good, and the bad. It all shaped me. ❤️

This made me cry hard. Thank you for sharing in doing so you reminded me of so much. I hope doing this helps with your grief, but doesn’t fix it because it’s an important part of life to love and to experience loss. Grief never gets fixed in my experience, but you sure show how to process it. thank you for your beautiful words. Big hugs.